No, It is Not Election Interference to Campaign in a Foreign Election

Also stop confusing legal and moral definitions of interference

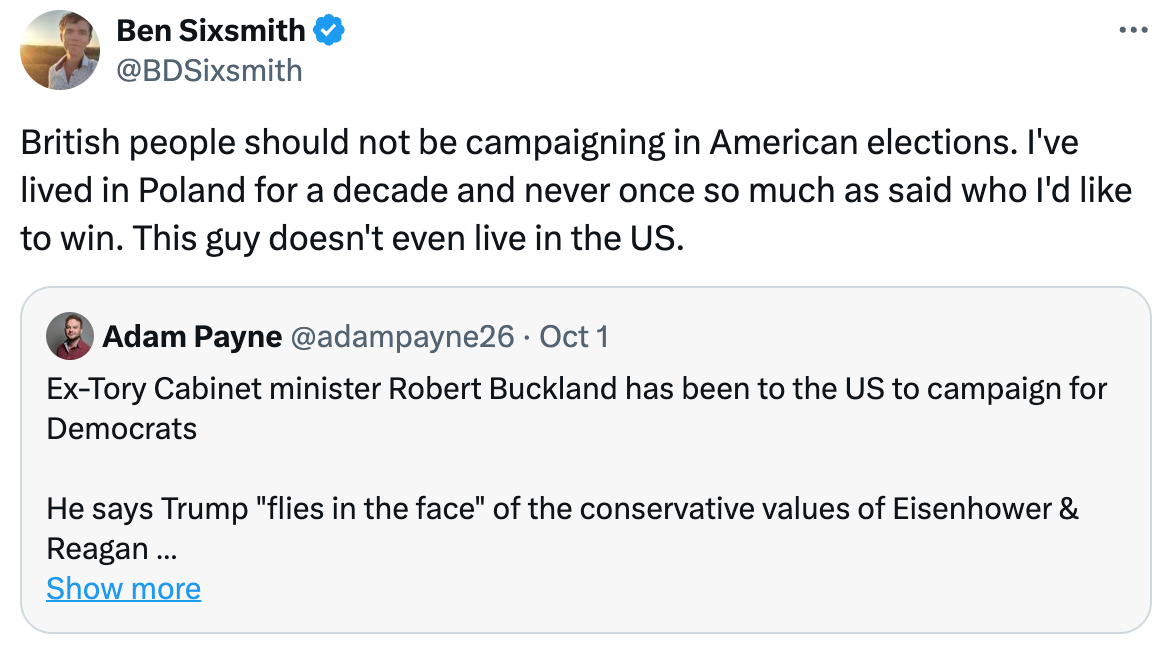

I have recently seen a number of tweets complaining that British people have been campaigning in US elections and considering this a form of election interference. In some cases, it has been claimed that this is illegal election interference:

In others, no claim of illegality is made and the objection appears to come more from an intuitive moral sense that it is presumptuous for people to express opinions on elections occurring in countries they do not live in or hail from.

I disagree with both the legal and moral claims expressed here.

Firstly, people campaigning for one political party or candidate - publicly making arguments for one party and against another - does not appear to be illegal and is not what is meant by “election interference” in a legal sense. Although the definition of ‘election interference’ is quite broadly defined as “when one nation acts to disrupt or influence the electoral process of another sovereign nation” this is generally understood to mean when the government of one nation takes action that subverts the democratic processes of another nation. Examples of such interference include bribery and coercion of government officials and material misrepresentation of factual information that citizens can be expected to factor into their voting decisions. It does not refer to citizens of one nation (including politicians) attempting to persuade citizens of another nation that one of its options will be better than another for its country. The citizens of the nation whose election is being discussed remain entirely free to consider, accept, reject or ignore the arguments of people from other countries and make their own informed voting decisions.

The UK acknowledges this distinction using the terms “pernicious interference” and ‘legitimate influence activity” and gives a hypothetical example of the former which involves an individual being instructed by a foreign power to obtain sensitive information on members of parliament which they then use to coerce that MP to vote and speak in ways favourable to the foreign power. “Legitimate influence activity” refers to attempts to influence people’s voting decisions by presenting them with straightforward information and arguments.

The US Federal Election Commission has clear boundaries around the involvement of foreign nationals in election campaigning which states that they may join and participate in campaigns as volunteers but must not fund them or direct their decisions or activities. Therefore, provided that members or representatives of the UK Labour or Conservative Parties do not engage in coercion or deception or take positions of management in US political campaigns but limit their involvement to assisting with providing US citizens with information and arguments for them to consider (or not) when making their voting decisions, this activity is legitimate and does not constitute election interference on a legal level.

Could such activity be argued to constitute interference on a moral level, though? That is, could someone object to “interference” not in the sense of illegal coercive and corrupt disruption of a sovereign nation’s democratic processes but simply on the grounds that other people should mind their own business? Yes, they could if the moral premise is that people should “stay in their own lane” and not offer opinions on the merits of the political parties of countries they do not live in.

I would disagree with this moral premise, however, because it relies on standpoint epistemology: the belief that legitimate knowledge is reliant upon identity and lived experience and that the opinions of people who do not have a certain identity or lived experience are not only illegitimate but presumptuous and interfering. This is the same moral intuition that underlies men being told they may not have opinions on issues that affect women, white people that they cannot evaluate what is and isn’t racist and people like J.K. Rowling being told that she cannot comment on trans issues because she is not trans. Somebody who has lived all their life in America is more likely to be able to speak to the experience of being an American than somebody who has never been there, but there is no single authentic political voice of Americans that fundamentally differs from that of non-Americans. This is demonstrated by Americans vociferously disagreeing with each other on the most fundamental aspects of US politics and doing so on the grounds of policies and principles also argued over in other countries.

I do not believe the value of viewpoint diversity stops at national borders, and the perspective of people removed from daily immersion in one’s own cultural narratives and media output can provide additional useful analysis for those who would like to hear it. Some Brits felt somewhat aggrieved by analyses by economists from all over the world on ‘Trussonomics” in 2022 but I, as a non-economist, appreciated being able to access a wider range of international analyses on this phenomenon. I feel confident that my own judgement and autonomy will not be removed from me if Americans or citizens from any other country travel here to endorse, campaign or argue for one party or another. I will listen to them if they are saying something I deem to add value to the discussion and I won’t if they don’t. It seems rather insulting to Americans to speak as though they are not also perfectly intelligent and capable participants in a democracy able to make their own choices about who to listen to and their own evaluations of which arguments have merit. Those who are already set against Kamala Harris are unlikely to be swayed by arguments made in her favour in a British accent and those who regard a second Trump presidency as potentially disastrous are unlikely to be moved from this position by the presence of Nigel Farage on his campaign trail.

I believe it is entirely legitimate for a British citizen to travel to the United States and take part in campaigning for a political party, provided this activity is limited to conveying information and making arguments that American citizens remain free to accept or reject on any grounds they choose, including that the speaker is not American.