No, Liberty Is Not the Right to Tell People What They Do Not Want to Hear

And Blocking Someone on Social Media Is Not a Denial of Free Speech

This piece is adapted from a response to a comment on one of my notes. The commenter, with whom I have since had a civil discussion and come to an understanding, made some claims about blocking on social media which fundamentally misunderstands the concept of free speech in a way which is all too common.

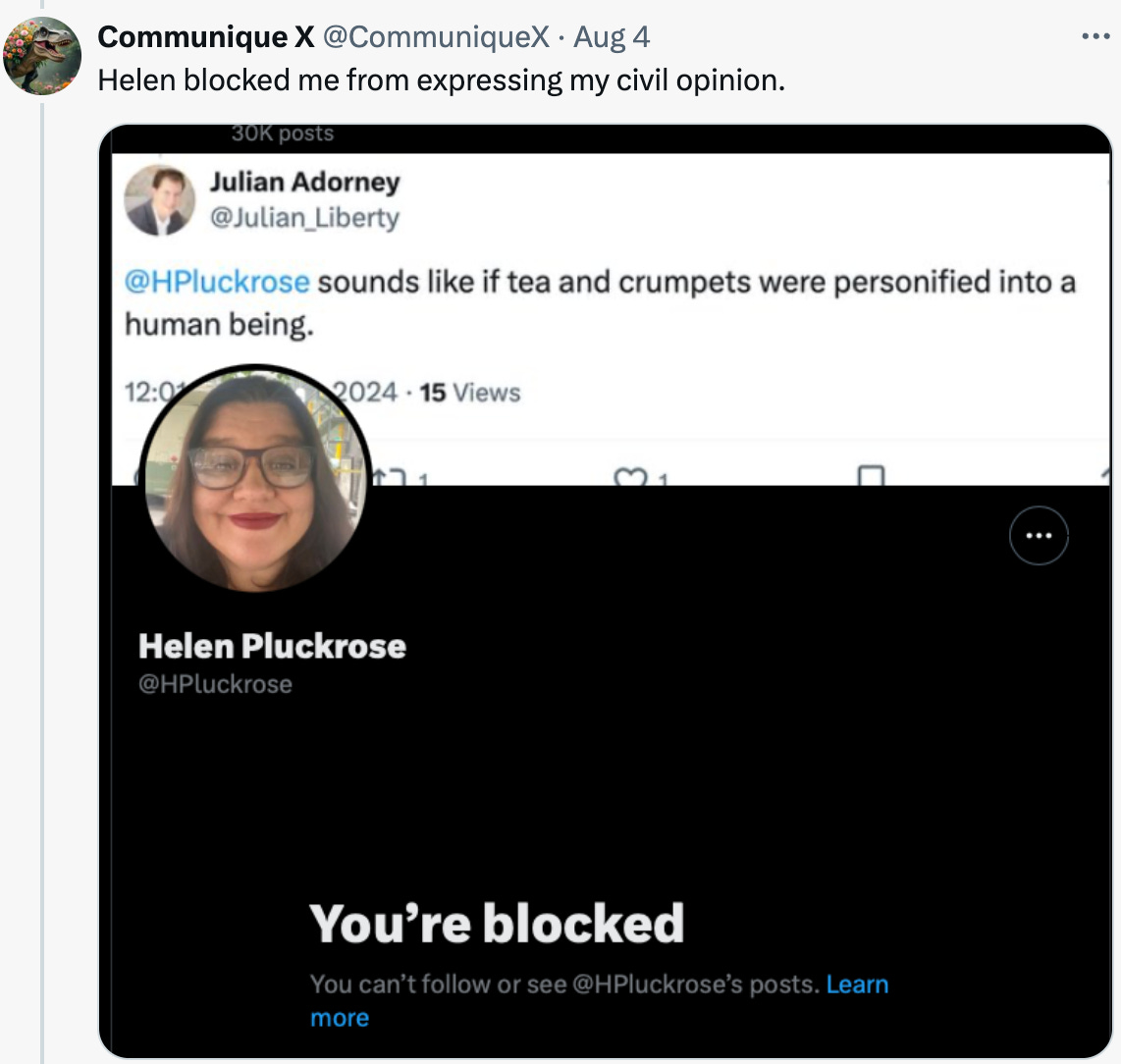

This error, at its most basic, typically looks like this:

No. No, I did not. The poster is quite clearly still there expressing his opinion, civil or otherwise. All that has happened is that I have gone away. People who make the claim that their right to express their views has been denied if somebody else chooses not to listen to them have really missed the ‘freedom’ aspect of freedom of expression. I have addressed this before, but the confusion about whether somebody who claims to support freedom of speech and find value in engaging in constructive disagreement is being hypocritical if they then choose not to engage with everybody who wishes to engage with them on social media continues to grow.

Something I find particularly frustrating is when people cite George Orwell in order to claim that compelling others to listen to you is the essential meaning of liberty.

“If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.”

This sentence must be one of the most commonly abused quotes ever and, stripped of context, is utterly opposed Orwell’s consistent stance on liberty and freedom of speech. Standing alone, it simply is not true. There is no right to tell people what they do not want to hear in a society that defends freedom of belief. Principles of liberty stand firmly in the corner of those asserting the right to choose for themselves what they listen to, whether it is the right to say “No, thank you” and close the door on someone asking if they can tell you the good news about Jesus or the right to decline to attend Critical Social Justice unconscious bias training. This quote of Orwell’s from the unpublished preface to Animal Farm, refers specifically to freedom of the press and the right to publish controversial ideas, not to compel anyone to read them. In this case, Orwell was defending his right to criticise the Soviet Union.

I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech – the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don't convince me and that our civilisation over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notice. For quite a decade past I have believed that the existing Russian régime is a mainly evil thing, and I claim the right to say so, in spite of the fact that we are allies with the USSR in a war which I want to see won.

Orwell was not demanding that any particular publisher who was not interested in his writing or disagreed with it should be coerced into publishing it. He was prepared to self-publish. Nor was he insisting that he had the right to make everybody read his book. He was deploring the resistance to the very existence of Animal Farm and that it was the supposed liberal intellectuals who should have been most protective of the freedom of the press who were making the objection.

But now to come back to this book of mine. The reaction towards it of most English intellectuals will be quite simple: ʻIt oughtn't to have been published.ʼ Naturally, those reviewers who understand the art of denigration will not attack it on political grounds but on literary ones. They will say that it is a dull, silly book and a disgraceful waste of paper. This may well be true, but it is obviously not the whole of the story. One does not say that a book ʻought not to have been publishedʼ merely because it is a bad book. After all, acres of rubbish are printed daily and no one bothers. The English intelligentsia, or most of them, will object to this book because it traduces their Leader and (as they see it) does harm to the cause of progress. If it did the opposite they would have nothing to say against it, even if its literary faults were ten times as glaring as they are….

The issue involved here is quite a simple one: Is every opinion, however unpopular – however foolish, even – entitled to a hearing? Put it in that form and nearly any English intellectual will feel that he ought to say ʻYesʼ. But give it a concrete shape, and ask, ʻHow about an attack on Stalin? Is that entitled to a hearing?ʼ, and the answer more often than not will be ʻNoʼ. In that case the current orthodoxy happens to be challenged, and so the principle of free speech lapses… . If the intellectual liberty which without a doubt has been one of the distinguishing marks of western civilisation means anything at all, it means that everyone shall have the right to say and to print what he believes to be the truth, provided only that it does not harm the rest of the community in some quite unmistakable way. Both capitalist democracy and the western versions of Socialism have till recently taken that principle for granted. Our Government, as I have already pointed out, still makes some show of respecting it. The ordinary people in the street – partly, perhaps, because they are not sufficiently interested in ideas to be intolerant about them – still vaguely hold that ʻI suppose everyone's got a right to their own opinion.ʼ It is only, or at any rate it is chiefly, the literary and scientific intelligentsia, the very people who ought to be the guardians of liberty, who are beginning to despise it, in theory as well as in practice.

We can certainly recognise this phenomenon of academics and intellectuals wishing to censor certain ideas that they believe will harm the cause of progress. I recommend reading the entire preface (linked above) because much of it will feel very familiar to anybody involved in our current culture wars. It is in this context of offering a challenge to the pro-soviet intellectuals that Orwell finished his essay with:

I know that the English intelligentsia have plenty of reason for their timidity and dishonesty, indeed I know by heart the arguments by which they justify themselves. But at least let us have no more nonsense about defending liberty against Fascism. If liberty means anything at all it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear. The common people still vaguely subscribe to that doctrine and act on it. In our country – it is not the same in all countries: it was not so in republican France, and it is not so in the USA today – it is the liberals who fear liberty and the intellectuals who want to do dirt on the intellect: it is to draw attention to that fact that I have written this preface.

Here, Orwell is not even insisting that the intellectuals he so harshly criticises be compelled to read his book. He simply anticipates that they will and that they will condemn it on dishonest terms by saying that it is badly written and will harm the war effort, while giving very little attention to whether its criticisms of Stalinism are justified. Orwell is speaking much more generally to the right to say and write things that people in positions of power do not want to hear because it goes against their narrative of progress (or any narrative) and condemning censorship on those grounds. He reminds us that it is the intellectual liberty to say what one believes to be true that has created the distinguishing features of Western Civilisation that those fighting a war against fascism were motivated to protect. That continues to be true today and is why we must continue to object to book bans and threats to freedom of speech more broadly and do so consistently even when they are imposed upon ideas that we ourselves do not believe to be ethical or true and wish to see die.

In our current age of social media, we must expand arguments for freedom of the press and oppose censorship and the banning of ideas to social media and insist that people have the right to express ideas and beliefs that others may not wish to read and wish did not exist, provided that they do not amount to the criminal harassment of an individual or do what Orwell calls unmistakable harm to the community. I have typically referred to this as material harm.

At the heart of the liberalism that underlies the ideal of secular, liberal democracy is one simple principle, best defined as,

Let people believe, speak and live as they see fit, provided it does no material harm to anyone else nor impinges upon their right to do the same.

It is important to have a clear understanding of and high bar for what constitutes material harm here. It cannot include beliefs, speech or actions which are considered subversive, hurtful, worrying, or bad for society. Authoritarians very commonly justify their authoritarianism by claiming it to be for the imposed-upon people’s own good. Every theocracy that has ever existed has claimed its heresy and blasphemy laws and its persecution of religious minorities to be for the good of society and even the heretics, blasphemers, and infidels themselves. The CSJ movement justified its no-platforming, cancelling, firing and intimidation of Gender Critical Feminists on the grounds that their beliefs and speech were harmful or even violent to trans people. People with a strong conviction that their own beliefs are true and good will frequently justify the suppression of those whose beliefs they perceive to be false and bad. It is not a good argument to say, “But my beliefs really are true and good” because everybody always thinks that. It would be incoherent not to.

This is not relativism which holds that all sincerely held beliefs are equally valid or have equal probability of being correct. It is liberal pluralism which holds that people have the right to hold a wide range of beliefs including those which are wrong. By protecting that right consistently and continuously, we uphold societal norms where the wrong are not denied their individual liberty and the right have a chance of being heard and effecting change when the dominant moral orthodoxy is wrong. As we can now see that there has never been a time in which the dominant moral orthodoxy was right about everything, it is important for the sake of both freedom and truth to hold that line.

The liberal thing to do if you encounter ideas or people that you do not wish to engage with on social media or anywhere else is to remove yourself from their proximity while leaving others alone to continue expressing their opinions to those who wish to hear them. In real life, this could look like choosing not to go to a talk at a university or a comedy show that addresses a subject or features an individual you find offensive rather than trying to “no-platform” them, have their event cancelled or blocking entrance or blaring horns to prevent anybody else from hearing them. It could look like saying “No, thank you” and closing the door or walking away from someone asking if they could talk to you about their religion or politics rather than trying to have them arrested. It could look like declining to be friends with or spend time with someone yourself rather than trying to have them socially cancelled. On social media, it looks like ignoring, muting or blocking people you yourself do not wish to engage with instead of reporting them or otherwise trying to get them removed from the platform. In this way, you remove yourself from the individual’s pool of potential listeners and interlocutors but, in no way, limit their ability to express their ideas and opinions publicly to anybody who wants to hear them.

Just as freedom of religion includes freedom from religion, so does freedom of speech include freedom from speech. We could think of the principle of freedom of speech as having four parts:

The freedom to speak - the right to express one’s own ideas and opinions without being arrested, fired, censored or cancelled.

The freedom not to speak - the right to choose not to share one’s own ideas and opinions and to decline to affirm anybody else’s.

The freedom to listen - the right to listen to other people expressing ideas that you want to engage with and that they have chosen to share with you, without anybody else impeding this and deciding what may be said and heard on your behalf.

The freedom not to listen - the right to choose not to listen to or engage with any set of ideas or any individual expressing those ideas rather than having them imposed upon you against your will.

I blocked the user above because I did not wish to engage with someone having civil opinions about immigration and cultural incompatibility while I was posting about rioters setting fire to migrant hostels with people inside, converging on mosques and causing them significant damage and physically attacking police officers and impeding firefighters from putting out the fires. Immigration and the issue of maintaining cultural integrity as well as the issue of when protesting is a legitimate right and when it crosses over into criminality are subjects that I am interested in discussing and have done so many times (including here and here). I am interested in speaking to people with whom I disagree on these issues but I reserve the right to choose who I discuss these issues with and in what context. This commenter did not strike me as somebody who addressed issues relevantly or thoughtfully and so I chose not to include him in the people I engage with.

The individual to whom I was responding in the comments of one of my notes had a different objection. He felt it was hypocritical of Andrew Doyle to have blocked him when Andrew is a strong proponent of freedom of speech and has a programme called Free Speech Nation. This makes the common error in assuming that someone who is committed to freedom of speech and engaging with a variety of ideas has a responsibility to engage with every proponent of every idea. Just as it would be ludicrous if Andrew were to claim that anybody who does not watch Free Speech Nation specifically would be hypocritical to consider themselves an proponent of free speech, it is ludicrous for any individual to suggest that Andrew or any proponent of free speech is hypocritical if he or she chooses not to engage with them specifically on social media.

This is where the value of thinking about this kind of engagement with differing views as a “Marketplace of Ideas” comes in. Inherent in that concept is the understanding that it is the responsibility of the individual who expresses or explores ideas to do so in such a way that other people are inspired to listen to them and evaluate whether or not to buy into them. If few people chose to watch or engage with Free Speech Nation, it would be Andrew’s responsibility to make it more interesting, engaging and relevant so that more people wanted to watch it, not everybody else’s responsibility to watch it whether they found it worthwhile or not.

There is a whole world of ideas out there and for each of the prominent ones, there are countless people arguing for or against them more or less well. Other people will gravitate towards the ones who are talking about the things they are interested in and whom they think are doing it well and choose not to listen to those whom they think are doing it badly. (This is how markets work). Just as in real life, this looks like choosing to attend one talk and not another, accepting one dinner invitation but not another, subscribing to some news outlets but not others, on social media, it looks like choosing to engage with, quote tweet, retweet or follow some people but ignore, mute or block others.

When you have a big profile on social media, blocking is often necessary because otherwise your notifications get filled up with the kind of engagement you don’t want to read. Muting doesn’t prevent this as even if you don’t see that individual, your notifications are full of people responding to them and this drowns out the thoughtful comments that you do want to engage with. The person you have blocked retains their right to speak to people who want to hear them and listen to people who want to speak to them. You have just opted out of doing so yourself. This is the ethical, liberal thing to do. (The unethical, illiberal things to do when you don’t like/aren’t interested in someone else’s ideas include things like trying to get them banned from the platform so nobody else can engage with them either and/or sending their tweets to their employer to try to get them fired).

If you are someone who wants to engage in the marketplace of ideas and have your ideas heard and engaged with, you have the responsibility to present them in such a way that makes other people want to do that. Nobody else has the responsibility to either be interested in what you want to argue or choose to listen to you arguing it rather than (or as well as) somebody else. You’re not being censored if someone chooses to opt themselves out of engagement with you. Nor is that individual closed to other points of view if they choose to engage with someone else’s counterviews rather than yours. If people opt out of engaging with you after reading something you’ve said, rather than knee-jerk blaming them for not supporting free speech, think about whether you can make your case in a way that makes people more likely to want to engage with it and with you.

As a longtime writer on issues of politics and culture, I have had some pieces go down very well and others sink like a lead balloon. When the latter happens, it simply means that I have failed to engage people on that occasion. It happens to us all and there’s no point feeling sorry for yourself or blaming your target audience for not having found your presentation of your ideas worth their attention. Time is better spent thinking about why they might not have done so and how you can make your case in a way that will make people want to read and engage with it. My advice to anybody who wants to engage with ideas publicly and have their views listened to, but finds they are being ignored, muted or blocked repeatedly is to recognise that, on platforms like social media and SubStack, a Marketplace of Ideas is in operation. If people aren’t buying your wares, they are probably not very good and the solution is to make them better. If you can make the argument that you want people to consider in a way that is engaging, persuasive, well-reasoned and well-evidenced, thoughtful people will engage with it. If you can’t, they won’t.

This is not a denial of freedom of speech. It is the exercise of freedom of listening.