Why You should Argue With People "On Your Own Side"

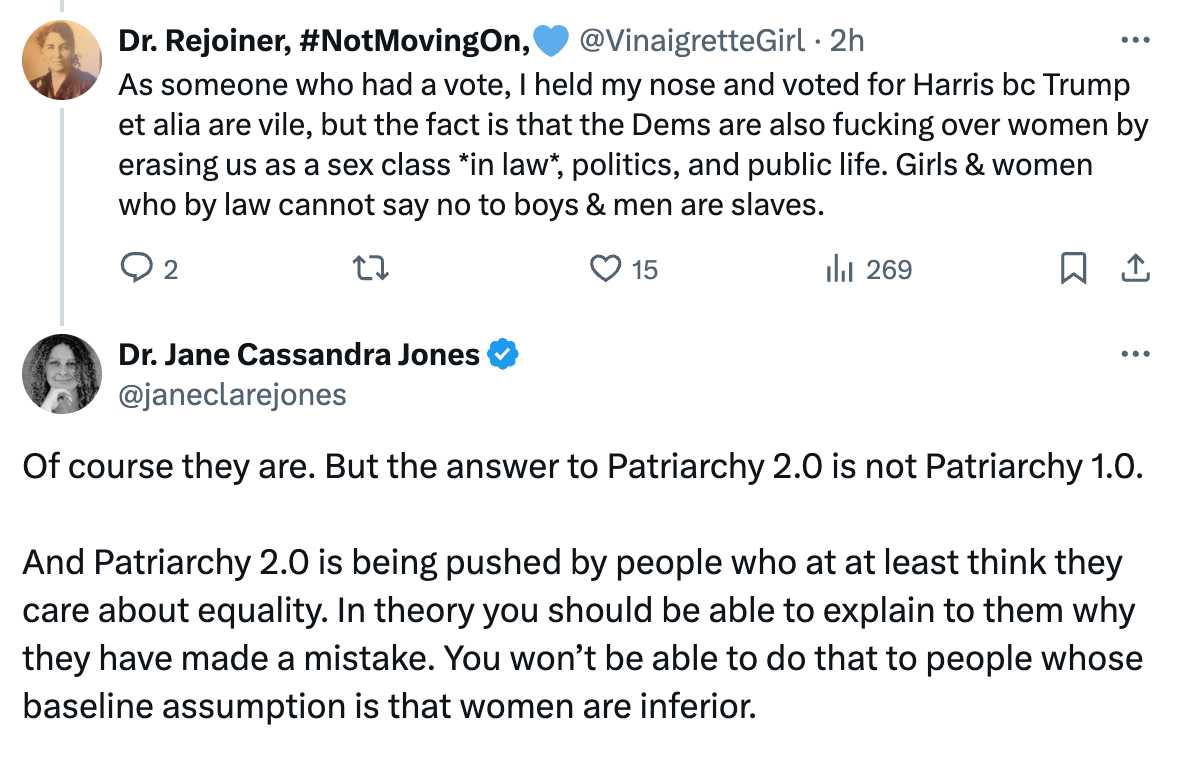

"In theory, you should be able to explain to them why they have made a mistake."

Today I came across this post by Jane Clare Jones which encapsulated a point I think people are increasingly inclined to miss.

Jane and I have disagreed on important issues in the past (as radical feminists and liberal feminists are prone to do), but I respect her principled consistency and clarity of thought. Most importantly, and relevantly, intellectually honest radical feminists and liberal feminists can disagree straightforwardly and should do so because we share a common premise and goal. We may disagree about the causes and nature of our current problem and consequently how to achieve those goals. It is essential that people who share social goals but differ on social diagnoses and methods can have these conversations because we cannot all be right. Being as close to right as possible on the nature of the problems we face and how to overcome them is very important to achieving the goal!

In the particular case of differences between radical feminists and liberal feminists, we share the premise that women are full human beings who merit full legal and social equality and all the rights, freedoms and opportunities that men have and the goal of overcoming any obstacle women face in achieving that. We may disagree on the extent to which obstacles to that goal still exist and on what the causes of them are. Consequently productive disagreement can happen and may look like this:

Radical feminist: I think your approach is too individualistic and freedom-orientated to the extent where it becomes unfocused and hinders effective organisation by women, for women and about women.

Liberal feminist: I think your approach fails to appreciate that social problems are ultimately rooted in ideas held by individuals to the point where it hinders effective organisation for women by alienating men who support women’s rights.

Unproductive disagreements can also happen and often look like this:

Radical feminist: You just hate women!

Liberal feminist: You just hate men!

This is because hyperbolic and deeply uncharitable mindreading is an individual character flaw and not the domain of any particular group, although I am inclined to think that a liberal mindset offers more protection from this than a radical one. In any case, it is profoundly counterproductive to achieving anything.

However, the distinction that Jane points out is absolutely crucial to understand much more broadly. In theory, we should all be able to have productive conversations with people whose basic premises and goals we share in a way that we cannot with people whose premises and goals are utterly opposed to our own. I am not speaking of the left and right as utterly opposed. As a liberal lefty, I have premises and goals in common with liberal conservatives as I set out here. We share an opposition to authoritarianism, a commitment to treating people as individuals with equal rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness and a preference for reform over revolution among other principles. We can and do argue about how best to go about this and this is productive precisely because we have shared premises and goals.

It is much harder to argue productively with someone who has entirely different premises and goals. I cannot argue that somebody is doing anti-racism wrongly unless that is what they are trying to do. If they actually think that racism is good and we need to do more of it, we are at an impasse. I can, in theory, reach the Critical Social Justice anti-racists, even if, in practice, they refuse to talk to me or assert that my disagreement with them indicates my white fragility and denial of my own racism. I may be unlikely to reach the true believers in those theories but my critiques may convince other people who oppose racism and are inclined to think the CSJ approach has merits that the liberal approach is stronger, more ethical and more tethered to reality. I have already heard from some former adherents of CSJ who tell me my critiques helped them find their way out when they began to have doubts. I cannot reach white supremacists. The people who have the best chance of making a difference there are cultural conservatives who can reach people who have concerns about cultural cohesion and are inclined to think that white supremacy might be an answer, and convince them it is not.

Similarly, I can, in theory, reach the Critical Social Justice queer theorists, even if, in practice, they refuse to talk to me and tell me that my disagreement with their approach amounts to denying people’s right to exist and trying to make them commit suicide. By engaging with their arguments nevertheless, I can reach people who are supportive of the rights of same sex attracted people and the gender nonconforming and inclined to think that the CSJ queer approach has merits and convince them that the liberal approach is stronger, more ethical and more tethered to reality. I cannot reach people who genuinely wish lesbian, gay, bisexual and gender nonconforming people not to exist and to tie everybody into rigid gender roles and stereotypes within a monogamous heterosexual marriage. The people who have the best chance of making a difference here are liberal social conservatives who can potentially convince others on the right with concerns about authoritarian queer theory that blaming sexual minorities for this rather than authoritarian ideologues is wrong.

The examples of this could go on forever, and seem quite self-explanatory and yet people all over the political spectrum and from a variety of ideological viewpoints seem not to find it so. Perhaps it is most intuitively graspable if I give the example that I, an atheist, am unlikely to be able to convince Christian Nationalists that they are doing Christianity wrongly, because they could immediately (and reasonably) point out that I don’t believe there’s a way to do it correctly. Christians, who share their premise that the Christian God exists and their goal to convince others that Christ is the way, the truth and the life, but who believe that Christian Nationalists are not behaving in ways that are Christlike are the people who can most effectively convince Christians inclined to become Christian Nationalists not to do that to the benefit of us all.

Why do some people seem to have so much difficulty grasping this? Why, when I first began criticising illiberal elements on the left did so many people assume I must hold values on the illiberal right? This assumption was made by both those on the illiberal left and the illiberal right with the latter feeling as though I had deceived them when it turned out that my claim to be a liberal lefty was true. Why, when I criticise authoritarian elements among gender critical feminists, did so many assume that I am an authoritarian trans activist or men’s right activist (or, bizarrely, both), rather than that I am, as I say, a liberal feminist?

I think the answer to this is that too many people seek to engage in political and cultural debate purely by highlighting bad things on the other side and they assume everybody else to do the same. Further, many actively believe that everybody else should do the same. They take up a purely oppositional ‘anti’ stance and require an utter collectivist solidarity with that stance and regard anybody trying to fix problems on their own side (and thus strengthen it) as a traitor supporting the other team. This is not new, of course, but it does seem to be growing and driving the intensifying polarisation and the increasingly hyperbolic and paranoid tribalistic narratives that both accompany and perpetuate that.

I think this ‘collectivist huddling’ and ‘allegiance testing’ reaction is a very human response to threat that has probably served our species well in its evolutionary past when survival really has depended on unwavering solidarity with an in-group and single-minded focus on defeating an out-group. I do not think it is serving us at all well in our current, complex sociopolitical environment. I think it is important to be alert to this threat response instinct and guard against it rather than throwing ourselves into it.

This is a time when it is particularly important that we maintain a strong sense of what we stand for, not only what we stand against and then to stand for that consistently against threats to it from wherever they come. Unfortunately, sometimes they come from inside our own groups or from people with whom we, at least, share basic premises and goals, even if we think they could not possibly have gone about it more unethically and counterproductively. It is natural too to feel more angry with those whom we feel should have known better than with those whom we never expected to know better in the first place. But to let ourselves be consumed by that anger to the extent that we forget those core premises and goals is a fatal mistake. It makes us vulnerable to mistaking the enemy of our enemy for our friend and shooting ourselves in the foot (or the reproductive system).

Helen: "I think this ‘collectivist huddling’ and ‘allegiance testing’ reaction is a very human response to threat that has probably served our species well in its evolutionary past when survival really has depended on unwavering solidarity with an in-group and single-minded focus on defeating an out-group."

Spot-on! And is reinforced, even today, by human physiology.

As Mark Johnson wrote in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 2021, "From birth we depend on the friendship and protection of others. Infants, "must instantly engage their parents in protective behavior, and the parents must care enough about these offspring to nurture and protect them," said [John] Cacioppo, the University of Chicago researcher."

"Even once we're grown we're not particularly splendid specimens. Other animals can run faster, see and smell better, and fight more effectively than we can. Our evolutionary advantage is our brain and our ability to communicate, plan, reason and work together. Our survival depends on our collective abilities not on our individual might." And thus, on the mutual protection and cooperation of the members of our tribe or band.

That dependency is reinforced physiologically. "Other threats to survival — hunger, thirst and pain — trigger messages to the brain that something is wrong and steer us toward solutions. Studies have found that loneliness prompts a similar warning, generating higher-than-normal levels of cortisol, a hormone released in response to stress."

Excellent. There are parts of this I am going to memorize in order to have at my disposal, should I find myself in an argument with one of the many people I love who are clinging to ideas, the implications of which they do not seem to understand. After all, Thanksgiving is coming.....